Are you serious?

Search your heart. What are you serious about? How far will you go?

It’s frustrating to not be taken seriously.

When I was a kid, one of my most agonizing frustrations was about how rare it was that anybody would take me seriously. It doesn’t bother me as much anymore, largely because I’ve since achieved some level of success at the things I care about. I now have some people who have my back – people who see me for who I am and what I’m doing – and I’ve also learned to be more patient with other people’s misunderstandings, misinterpretations, and so on. I’m writing this to share some of my thoughts about that.

I think I got partially radicalized by the books I’d read. Good books are written by serious authors, and being deeply immersed in their work stirred something in me that made me yearn to live a serious life myself. It just seemed so obvious to me that a serious life is a life well-lived, and it’s always been weird to me how uncommon this perspective really is. Sure, you can catch snippets of it in all the motivational speeches and slogans that people throw about:

“The world has the habit of making room for the man whose words and actions show that he knows where he is going.” – Napoleon Hill

“The future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams.” – Eleanor Roosevelt

…but mostly people seem to use it as window dressing, rather than, something to actually take seriously. This disparity is something that’s haunted me all my life, and I’ve sought to understand it, and I think I have a pretty decent (albeit always imperfect) understanding of it.

We do live in a world that’s full of unserious people.

As I got older it became clearer to me that not many people are really serious about anything. Some people go their whole lives without ever having met anyone else who I might describe as actually serious, so they find it hard to believe that anybody could really mean what they say, since everything everyone says is bullshit. I remember feeling like that myself at some of my low points in life, when I was at my most depressed.

Looking back now I don’t think I was entirely wrong, the issue was that I was overly fixated on unpleasant truths. I find myself compelled to describe it as “LinkedIn World”, where everyone is performing a bullshit role in a bullshit play. And my blessing was that I did still have a little light in the darkness from the authors I mentioned earlier, which felt like a glimmer of honest earnestness. And that glimmer has kept me going through everything.

(Even that isn’t the whole picture, since there was definitely bullshit in that scene too, as there is in all scenes – but there was also a truth to it.)

Anyway so– it’s actually quite rational for most people to assume that any other random person probably isn’t serious. That they don’t really mean what they say. Lots of people play-act seriousness for social reasons, but quit when the going gets tough. So it makes sense that lots of people are broadly cynical. Cynicism is a completely reasonable defense against fraud and bullshit. The trouble with cynicism as a defense mechanism is that you can get so good at it that you inadvertently also defend yourself against anything good happening for you. But back to seriousness…

Serious people do exist. Let me tell you about some of them.

Justo Gallego Martínez was serious. At about 36 years old, he got stricken with tuberculosis, got better, promised God that he would build a cathedral, and spent the remaining 60 years of his life building it. "When I started building, word on the street was that I was crazy. They didn't believe I would be so dedicated... I'm proving them wrong."

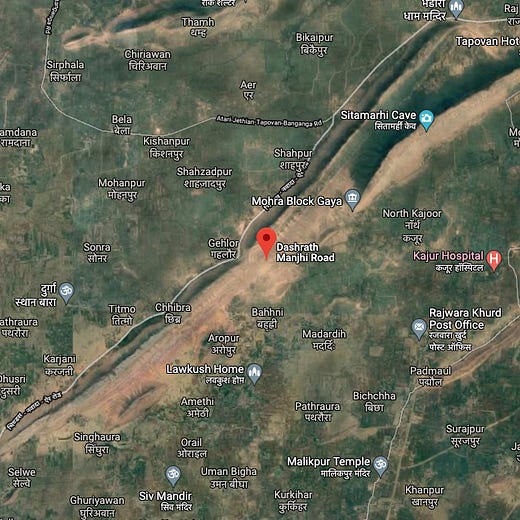

Dashrath “Mountain Man” Manjhi was serious. In 1959, Dashrath Manjhi’s wife died from her injuries after a fall, being unable to get medical attention in time. He spent the next 22 years using a hammer and chisel to carve a 360ft path through a mountain, reducing the distance between his village and the nearest doctor from 55-70km to 1km. "When I started hammering the hill, people called me a lunatic but that steeled my resolve." You can see the impact of his efforts on Google maps:

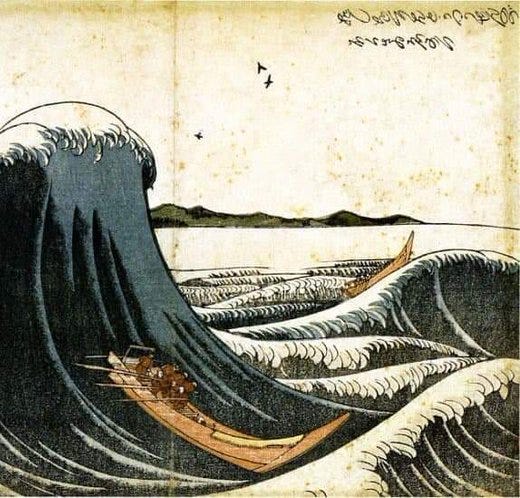

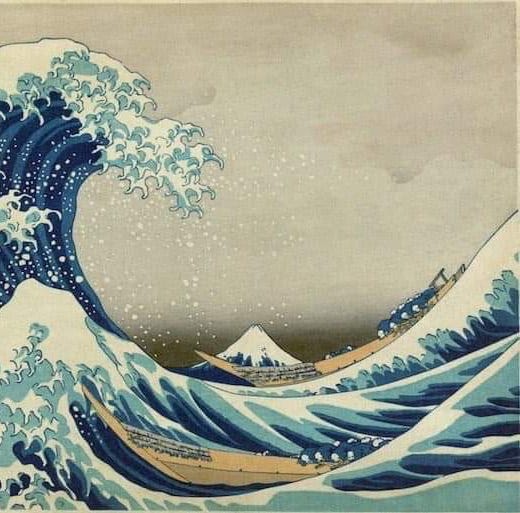

Hokusai was serious. Here’s him talking about his paintings after ~70 years of working on them: “From the age of six, I had a passion for copying the form of things and since the age of fifty I have published many drawings, yet of all I drew by my seventieth year there is nothing worth taking into account. At seventy-three years I partly understood the structure of animals, birds, insects and fishes, and the life of grasses and plants. And so, at eighty-six I shall progress further; at ninety I shall even further penetrate their secret meaning, and by one hundred I shall perhaps truly have reached the level of the marvellous and divine. When I am one hundred and ten, each dot, each line will possess a life of its own.”

Here are two of his paintings, you might recognize one of them:

I could go on and on – Gertrude Stein was serious, Erasmus was serious, Mandela was serious… I have a list of hundreds of people throughout history who’ve inspired me with their focus and their devotion – that’s part of how I know that I’m serious about understanding who’s serious, how to be serious, etc. This is a talking point I keep returning to. You can actually do the reading. You can get surprisingly far with this.

You can only really find out who’s serious over time.

This is true internally too. Fraud and bullshit aren’t the only problems with play-acted seriousness – even when we’re being maximally truthful, we often don’t know what seriousness in some context even is, until we’ve experienced it ourselves.

I would like to describe myself as serious, but… part of the whole point of this essay is that talk is cheap. Anybody can say that they’re serious. How can I demonstrate that I’m serious? Well, I could point to work that I’ve done. When I was 22, I decided that I wanted to become a good writer, and that doing that would require doing a lot of writing. So I started a writing project called 1000wordvomits, where I set out to write 1,000 stream-of-consciousness essays of 1,000 words each. 10 years later, I’ve written 821 out of 1,000 essays, and I intend to complete them. I’ve similarly made 200+ youtube videos and I intend to make over 1,000 of those, too – at least one a month every year for the rest of my life, or as long as YouTube exists.

I haven’t lived long enough to really demonstrate just how serious I am, and I hesitate to say it because seriousness is something that really you can’t tell from an utterance. You can mainly only tell from watching how someone conducts themselves over an extended period of time. Over decades. Particularly, how they deal with shocks, rough times, downcycles. Everyone is optimistic when times are good. The thing to look out for is who keeps going when the going gets tough.

In one of my previous essays about earnestness, I linked to a poem that I wrote when I was 20 that’s basically about how serious I wanted to be. While it’s janky and overwrought, 12 years later I still stand by every word that kid wrote, and I believe with full conviction that I will continue to be proud of that kid for as long as I live. Earnestness is daring to be serious about your feelings.

When I say serious I don’t mean solemn and tedious.

I mean something closer to ‘dynamic persistence’, and a sense of humor is often critical to that. It’s hard to persist for a long time if you ‘take yourself too seriously’. You become rigid, stiff, the opposite of dynamic, and eventually you bang up against something that breaks you one way or another, because you weren’t able to back down, or laugh it off.

So the point is to take the work seriously but you don’t take yourself too seriously. There’s a riff about this in Stephen Pressfield’s War of Art, where he talks about how amateurs are too precious with their work: “The professional has learned, however, that too much love can be a bad thing. Too much love can make him choke. The seeming detachment of the professional, the cold-blooded character to his demeanor, is a compensating device to keep him from loving the game so much that he freezes in action.”

The word ‘amateur’ comes from amare, ‘to love’, and I will be the first to readily admit that I can be very precious about my work! I’m almost definitely a more precious than what would be ideal. But the point is to not be so precious that you choke. I’m still publishing. That’s the litmus test. Are you publishing, whatever publishing means to you? I want to see it!

This tension is also part of what I’m getting at with the “ayy lmao” meme – “excruciatingly meaningful” is when everything you do or don’t-do is so overwhelmingly important that it paralyzes you – or worse, convinces you that it’s okay to treat people poorly because your quest is of such cosmic significance.

Solemnity is pomposity, is arrogance, is rigidity. We can be serious and we can have fun, joke around, be playful, silly. I even like to argue that silliness is sacred, in part because it keeps thing dynamic and fresh. John Cleese had a great bit on this too:

John Cleese: “Now I suggest to you that a group of us could be sitting around after dinner, discussing matters that were extremely serious like the education of our children, or our marriages, or the meaning of life, and we could be laughing, and that would not make what we were discussing one bit less serious. Solemnity, on the other hand, I honestly don’t know what it’s for. I mean, what is the point of it? The two most beautiful memorial services that I’ve ever attended both had a lot of humor and it freed us all and made the services inspiring and cathartic. But solemnity, it serves pomposity. And the self-important always know, at some level of their consciousness, that their egotism is going to be punctured by humor. That’s why they see it as a threat.”

There’s also a great anecdote from Nobel-winning physicist Richard Feynman, where he talks about how physics used to delight him when he used to play with it, but then it started to disgust him when he got burdened by this idea that he was obligated to advance the future of science. That he was supposed to be doing “important” work.

It’s quite poetic how, he only broke through his malaise when he decided to give up on the whole enterprise of “doing important work”, and simply started fooling around for the sake of it – and even more poetically, it was his fooling around with wobbly plates that led to the equations that he won the Nobel prize for!

It’s worth reflecting on this one for a bit. For Feynman, taking physics seriously meant being playful and silly with it. As I revisit my own drafts and notes, I often find the same issue – I want to write essays that mean something to me, but when they become tedious, solemn obligations, then I don’t wanna. That’s the tension to navigate. It’s not complicated.

If you’re serious, you will optimize for survival, because you can’t keep playing if you’re dead.

One of the stupidest things I’ve repeatedly seen smart people do – I call this Advanced Stupid – is that they get so fixated on trying to optimize something complicated, that they forget to optimize for survival, and then they get knocked out of the game. Like having a startup trying to do something complicatedly clever, and then running out of money. The thing here is to study the failure conditions – how and why have past players failed to do what you’re trying to do? – and be conscientious about avoiding that.

You do the reading. You look up your predecessors and study why they succeeded, why they failed, what worked, what didn’t. You recognize that whatever understanding you have is provisional, piecemeal, wrong and not-even-wrong to degrees that you cannot understand. If you’re serious, you’ll work at managing your psychology such that you stay motivated to keep going, because if you run out of juice, you’re out of the game. You recognize that your day-to-day motivations will likely change, and prepare for this. You’ll periodically review your behavior to see how things are working out for you. You’ll learn to think about constraints.

It’s not easy, but it’s not ridiculously complicated, either. I remember experiencing waves of euphoria at some point when it became clear to me how simple it all really is. But of course, simple doesn’t mean easy. Bullshit is easier.

On the problem of stolen valor polluting the commons

From time to time I get very angry about the idea of stolen valor, by which I mean people claiming and pretending to be serious when they are not. I probably still have some personal issues to work through here, but I don’t think I’m crazy or wrong to be mad about this – people who are loudly, publicly unserious pollute the commons by making everyone else a little bit more cynical in response. This makes it harder for any kid to be taken seriously, which in turn means that as a society we get less of the glorious output of serious players. We crush the caterpillars and complain there are so few butterflies.

There’s some complication to get into about fraud, delusion and the problem of knowledge. Even if we could somehow successfully discourage all bad actors from their stupid bullshit, we do still have to deal with more foundational problem of knowledge, which is that there are ways in which you cannot know if you’re actually serious until you’re in the thick of it. There’s a kind of cruel injustice here about the nature of life itself, of being a mortal, a finite being with limited knowledge.

When I talked about this with my ex-boss Dinesh, he said, “You never really know what being serious means in your context till you try to be serious. So people might in good nature start out wanting to be serious. But you might not prepared for the fact that your notion of serious is going to possibly change quite radically and disillusion you.”

I’m in two minds about this. On one hand, some amount of it is inescapable, and it is very, very important to anticipate dealing with the inescapable. Life has a surprising amount of detail. But on the other hand, so much of it IS avoidable, too. Literally by doing a little preparation. Yeah, you can’t prepare for everything. But you can prepare for a lot, in a surprisingly short amount of time and space, if you’re methodical and thoughtful about it.

This is where I get to this strange situation of… am I being too harsh? On myself? On others? Are my expectations too high? I don’t think so. I think I just want more out of life than most people do. And I don’t say that to flex on anybody, if anything I’ve come to become kinda sheepish and embarrassed about it. You could say that I was infected with brain parasites, from all those books that I read as a kid. I’m choosing to write an essay about it in part because I don’t like subjecting random people to it mid-conversation. I don’t want anybody to ever feel bad because of me, or feel like they’re not-enough, not doing enough, etc etc.

The solution here is to have clear boundaries and to communicate them clearly. For me, that looks like this:

You’re completely welcome to think that I’m full of shit, or that I’m unlikeable, or overwrought, dramatic, annoying, arrogant, all of that stuff. You’d be right! I used to be rattled hard by negative feedback, and I would to twist and bend to try and accommodate everyone, and that actually often made things worse. So now I’m finding that it’s easier to say, look, this is what I care about, this is the game I’m playing, you don’t have to play it, you don’t have to like me, cheers, have a nice day.

It’s pretty funny when you see how, being comfortable with being disliked, actually makes you even more likeable. It’s one of the many ways in which life can be really unfair.

Seriousness in relationships

Navigating conflicts about disparities (and perceived disparities) in seriousness can be very contentious. It can maim relationships – people have vicious, ugly fights over it, and sometimes they end relationships over it, and sometimes they don’t when they probably should. “I wish you would take this seriously” is a request that can get parsed as an attack. And sometimes people don’t know how (or are unable) to make that request in a kind, gentle way, and so they go for the attack.

Marriage is a serious proposition. It’s a commitment for life. And… a lot of marriages do end up in divorce. And I really, really don’t want to offend or upset or hurt anybody when I say this, I say this with love and sadness… the fact that so many marriages end in divorce is, to me, further proof that we are not very serious. I don’t say this to victim-blame people who have suffered in unhappy marriages. I think divorce can be a good thing, and I have cheered full-heartedly for friends who have separated for the better. I think what I’m trying to say is that we’re pretty unserious as a species. We don’t do enough to prepare ourselves for such a serious endeavor. I call this “the divorce mystery” – why do so many people divorce someone they thought was their favorite person? It’s not really a mystery: it’s mostly because good times are a poor predictor of how you’ll handle bad times. But as a species, as a culture, we have not truly internalized this.

And… I think we can improve it! I think we can do better. That sounds like an idealistic teenager thing to say, but I’m in my thirties now, and I believe I will continue saying this for as long as I live. I believe we can improve the human condition. We are culture workers, some of us more conscientiously deliberate than others. With our actions and our utterances we contribute to the building of culture. This is one of the things that I’m serious about. I’m willing to die trying. The work will not be done in my lifetime, or the next, so it’s important to enjoy the process.

You can’t demand seriousness from other people.

You can really only encourage it. You can’t bully people into becoming truly serious, because even if you ‘succeed’, they’ll mainly internalize that bullying is how you get things done – and they’ll likely get twisted up about performing seriousness, rather than being serious. So the best way to encourage it is to demonstrate seriousness yourself, in your own words and actions. Review your own life, and ask yourself what you’re serious about and what you’re not. Strive to be honest with yourself and others.

Parents often try to demand seriousness from their children, and fail. Spouses often try to demand seriousness from each other, and fail. I’ve lost friends from the bitter fights that can arise when you try to discuss this stuff with people who haven’t yet developed the finesse of navigating one’s deep emotional and psychological wounds. I look back on some of those with grief, because oftentimes those friendships were borne out of a seeming mutual interest in being serious together. But again, talk is cheap, and the road is long, and you’ll see for yourself along the way who sticks around and who calls it quits.

I do think it’s important to be gentle and kind with people who quit. No matter how great any of us might be, it is true that we’re all some accident or event away from not being able to keep going. There is no reason for cruelty, harshness, judgement, etc.

If we want to build great scenes that produce great work, we need serious people to be honest with themselves and each other. I am committed to spending the rest of my life trying to be a beacon for serious players to find and connect with each other. And in my model, if you’re serious about your work, you also have to work through your personal issues – you have to be kind, you have to be gracious, and so on – so that your work can really shine.

Seriousness is love and curiosity expressed earnestly.

I took a bit of a roundabout way to get to saying this but I mean it.

This sets my earliest statement in an interesting light, doesn’t it? “It’s frustrating to not be taken seriously” becomes “It’s frustrating to be treated without love and curiosity”. And here I feel this deep sadness at realizing how lonely and despondent I felt in my formative years, but also a deep gratitude for the books and art and music that kept my soul alive. And I feel a rekindling in my heart to pay it forward.

It renews my convictions. I want…

to be as serious as I can about the things that matter to me,

to be encouraging to everyone else who wants to be serious too,

and to be kind to everyone who doesn’t quite manage to be.

❤️🔥💪🏾

If you liked this essay, you’d also like my pdf ebook INTROSPECT, which you could read as a guide to taking yourself seriously.

While I was writing this, I rewatched a video by jazz pianist Kenny Werner, and I was really struck by his ability to be so gentle and ruthless at the same time, in a way that's loving and no-bullshit, and also economical. I'm trying to strike my version of that balance, but I think I still need more practice. I think I'll always think that. And I think that's probably for the best.

EDIT: I was going through old notes and found this: "i spent so much of my life frustrated at not being taken seriously, that for a long time i tried to take everyone else as maximally seriously as possible, and funnily this too led to a bunch of crappy outcomes".

"We crush the caterpillars and complain there are so few butterflies."

You have a hell of a way with words, my friend. Really enjoyed this piece.