I’ve had the mental image of scaffolding on my mind for a long time, and even a pinterest board about it for some reason. I think the reason is, at some level I’m hoping that looking at scaffolding might trigger some sort of insight or understanding about scaffolding. (A previous post, signposting thru it, uses one such pic).

If you’re trying to build anything substantial, you’re going to have to use some kind of scaffolding.

You need to have some sort of container, some sort of meta-structure that facilitates the building of the main structure. my feeling is that… i’ve always been quite bad at this. i tend to use as little scaffolding as i can manage, and often my projects fall apart because of improper or insubstantial scaffolding.

Now, let me be precise– oftentimes, projects simply aren’t meant to be finished. Lots of creative projects are best thought of as ‘drafts’ (rather than ‘false starts’, which I consider to be a misuse of a sports metaphor, inappropriately ported over to the creative realm1). The purpose of a draft is to function as a kind of scaffolding. It’s a sketch, an outline, a way for the creator to think through their project, to make mistakes cheaply.

For example, if you’re sketching a bunch of drawings of hands in varying positions, it makes more sense to sketch the shape of each hand and then move on to the next sketch, than it does to go through the trouble of ‘finishing’ by meticulously shading each sketch. The goal is to get a better understanding of hands, and the shading takes time and effort. You draw 20 different ‘low-res’ hands and it improves the quality of the hand that you draw for the ‘real thing’ that you work on later. Or maybe you just enjoy the process of getting to know hands better.

Of course, you might also want to get better at shading, in which case it might make sense to practice doing 20-30 different shading exercises– for starters you could practice shading fruits (or even perfect spheres), which I believe are comparatively easier to draw than hands. Even if the desired end-goal is a polished drawing of a well-shaded hand, it might make more sense to practice drawing hands and practice shading separately.

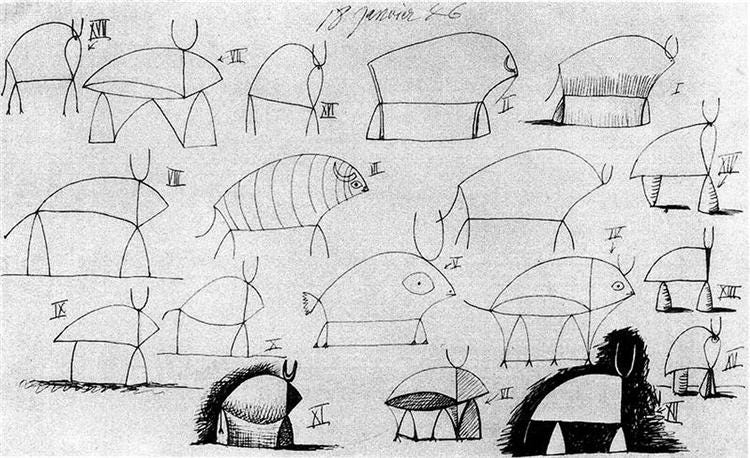

Above are some of the setches that Da Vinci did while working on a a couple of compositions of Leda and the Swan. The paintings are lost, but there are many copies that other painters have made– it’s a fun little rabbithole to get into.

Anyway, what I find interesting is to try and follow Da Vinci’s thinking as he made these sketches. What was he trying to accomplish? The first is comparatively small and crude– it looks to me like he was mainly figuring out the pose and the composition, and you get a sense of the whole.

In contrast, in the third pic, he does the (disembodied) head several times. It looks to me like he probably did the low-res face (bottom left) first to get the face-and-hair combination roughly-correct, then tried drawing the hair from a couple of different angles (probably the less-detailed one first), and then the main study on that page is the one with the beautifully detailed expressive face, probably close to what he might’ve done in the final painting.

to do good work, you have to do good project management

After spending some time looking at Da Vinci’s sketches, I find myself wanting to state the following more assertively than I otherwise would have: It seems obvious, maybe even tautological, that anybody capable of producing great work, has to be capable of doing this kind of project management effectively. Because we have a limited amount of time and energy, if we want to get good, we have to allocate those resources effectively. And to do that we have to know how not to waste our time polishing turds2.

I think it can be tempting as a novice to assume that everything a master produces must be refined in the high-res, high-production-value sense. I think that would be quite definitively wrong. A master has to be capable of producing quality low-res work, experimentally. And here I suppose I should clarify that I’m talking about artists in the risk-taking sense, the kind that Baudelaire described as barbaric and/or child-like. Good works are familiar, pleasing, refined, they meet our expectations. Great works are unsettling, disorienting, they confound our expectations. In this definition, it’s almost impossible for a great work to be considered ‘refined’ at the time of its creation, because its elements are alien, they have not yet had time to have been weighed and evaluated.

I think the principles of great project management are probably a little less varied than the principles of great work, because the human being is constrained by mundane things like needing to eat and sleep. Some experimentation there can be interesting, and some artists go hard on that, but generally speaking it makes more sense to live a robust life. Flaubert had a quote that went, “Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” I think intellectually this makes a lot of sense. I suspect I would be more violent and original in my work if I got more physical exercise and more sleep. I know all this intellectually, but emotionally I must confess I do sometimes fantasize about pulling a deranged all-nighter and producing something magical in a fugue state. Salvador Dali would allegedly do things like nap in a chair while holding an object that would wake him when he dropped it, so he could work with his dream-state. That’s something that’s always intrigued me, but I never quite got around to really experimenting properly with it. I’m not sure if I’ve said it on here before, but I sometimes feel like I have some kind of aversion to “being a precious diva”, and that that probably has kept me from experimenting more with my process. I suspect I could probably reframe it as “being a cheeky lil trickster” and, it gets so recursive, trick myself into having fun with it. We’ll see.

If you’re having fun in your work,

then almost nothing else matters

Earlier I laid out my hypothesis for how one ought to practice sketching and shading separately– but I think there’s a principle that supercedes the one I described, which is– if there’s some odd way that you particularly enjoy doing things, then you should probably prioritize that over any system that anybody else advises you to do. Because even ‘polished drawing of well-shaded hand’ is merely an intermediate step in a much larger lifelong journey of being a creative.

I’ve definitely encountered people who worked really hard to produce some polished artifact, only to then find that they’ve burnt themselves out in the process, and no longer feel like producing anything. Which… isn’t necessarily the end of the world; maybe that’s how you learn that drawing isn’t what you want to be doing, and maybe you can then release that ‘obligation’, however strongly or lightly you were holding on to it, and then move on to something else you might rather be doing.

Feel like I didn’t quite hit the spot here so let me try again– if project management is the meta of doing work, then managing your psychology is the meta of project management. A moderately-good process maintained over years tends to bear much better fruit than an highly-productive process that one cannot sustain for more than a few weeks or months. Fun, laughter, mischief, amusement– these tend to be reliable indicators that something good is happening. The absence of those things tend to be an indicator of the opposite. I’m reminded of a line from Before Sunset, where Jesse is telling Celine about how he loves his son, but there’s no joy or laughter in his home because of his failing marriage, and she’s sorry to hear that, because even when her parents had bad fights, they were always laughing. I think this applies to the creative process, too. And this is why I put “ayy lmao” in my meme about the heart of philosophy. Laughter is the divine thing that transmutes stupid bullshit into something real. It cracks up the edifice of polite fictions and tedious prattle and gets to the heart of things. And fun, I think, always has a spirit of laughter about it, even if you’re doing it quietly with a blank expression. It’s the soul that’s delighting on the inside, like children playing.

postscript: some thoughts on music

Let me switch to talking about music for a while, since it’s something that I once actually devoted a moderate amount of time and energy to. I’m not the best musician around, but I went from being a complete noob to being somewhat-passable3. There’s a bunch of things you can practice. I believe it’s best to start really simple. I would recommend a total beginner learn to play the simplest possible songs as quickly as possible, because it’s satisfying to feel like you’re capable of doing that. You don’t really need to know all of the notes on your instrument. And you don’t really need to learn all the chords and so on.4

Looking back at my progress over the years as a musician now, I’m kinda surprised at how little I learned, and how slowly, ‘despite’ all my grunting and straining. But I see now that the grunting and straining actually gets in the way. The fear of making mistakes is a particularly strong dampener on one’s learning. You can’t learn if you can’t make mistakes. I like the idea that mastery is simply a very intimate understanding of all the possible mistakes one could make. Daniel Dennett had a great riff on this– he recommended being a connoisseur of one’s mistakes. Bass virtuoso Victor Wooten points out that anytime you play a note that you don’t like, on either side of that note is another note that you do like. So correcting a melodic mistake in music can almost always be a matter of sliding to the next note. I suspect that the masters of rhythm have something similar– Dizzy Gillespie had a bit about how he kept time with his entire body, such that any time he played any note, it would be correct. I don’t claim to properly understand what he meant by that, since I still make mistakes all the time when I play– but I can try to approximate an understanding via proxy. I might jokingly say, “any time I write a tweet, it is correct.” I don’t mean the content of the tweet is necessarily correct in a factual sense, I mean that I’ve immersed myself sufficiently in the game of tweeting that I have a fingertip sense of what a good reply to something would be.

I think there’s something powerful and potent waiting for me in “I’m kinda surprised at how little I learned” that I still haven’t faced the full emotional truth of. I think there’s something about how little progress I made as a musician, and how long it’s taken me to write posts for this substack, and to get out of the neighborhood of posts i’ve written so far.

Now, I’m not being fake-humble here, and I’m not looking for sympathy (“No, you didn’t take that long! it takes at long as it takes!”) or encouragement (“You got this! I know you can do it!”). This is just my honest assessment of my own work ethic, my own meta attitude towards my work, etc.

In domains like athleticism, you could look at someone’s exercise plan and say, “Yep, that guy went to the gym 3 times a week for 10 years and he hardly made any progress on his fitness goals”, and it would be something people could analyze with some degree of objectivity. Like, oh yeah, you’re not hitting your major muscle groups, you’re not eating enough protein, you’re not using enough weight, etc.

While I have already established that I don’t believe that sports and arts are straightforwardly interchangeable, I don’t believe they are entirely alien to each other, either. There are similar critical observations we can make of someone’s creative corpus: oh yeah, you’re not identifying the most salient bits in your pieces, you’re not asking enough questions, you’re trying to say too many things at once, you’re not describing things in enough detail, and so on.

That’s about the work itself. And then there’s the meta, which is less visible, so it’s hard for anybody to give you feedback on. Even if you go to a therapist or an editor or a coach, chances are they won’t really get to see the truth of things, they’ll only see what you show them, which will to some degree be an incorrect representation of the truth, even if you’re actually trying your best to be honest. The good ones will be aware of this and price it into their appraisals. Even so, it’s all really tricky business, which explains a lot of why the rate at which people self-actualize into superstar performers in any domain is pretty low. Part of my grand vision for my life’s work is to try and help to increase that rate, but if I’m going to do that, then I ought to figure out how to do it myself, first. And I do that being joyful and mischievous in the scaffolding is a part of it. We’ll see.

I remember experiencing a great relief the day I realized that ‘false starts’ was a bad metaphor in the creative realm. Art is not a timed race. There is no starter pistol.

Re: ‘polishing turds’, the devil is in the details. In the beginning you might waste a lot of time trying to improve something that simply can’t be improved, especially not at your skill level, and in that stage it would make more sense to just try again differently. And if the cost of trying is high, it makes sense to try in a minimal way. If you’re painting, for example, paint and canvasses etc aren’t cheap! “Make mistakes as cheaply as possible” is one way of thinking about this. O course, you also want to actually be learning from your mistakes as you go, which requires that you be present and pay some amount of attention.

I hesitate to call myself a musician, although I did play in bands, I did write, perform and record original music, I have been paid money for performing live– so I’m at least ‘more serious’ of a musician (quasi-semi-pro?) than I am an illustrator (complete novice/amateur). I can point at all these things I haven’t done, though. I can’t sightread musical notation, I’m not too good at improvising on the spot (though I can play most chords if I get the opportunity to rehearse, or if my bandmates call them out), I’ve never done any session work (recording for other people). I know there are some guru types who say, “if you play music, you’re a musician, if you put pen to paper, you’re an artist.” Akira Kurosawa said all you need to write a movie script is paper and a pencil. There’s truth to that. The label ‘author’, ‘musician’, ‘illustrator’, etc can all be kinda distracting, limiting. Real quick I wanna note that I love the (true) story of how Kanō Jigorō, the founder of Judo asked to be buried with a white belt, because he wanted to be remembered as a lifelong learner. On one hand I think that’s beautiful, on the other hand I think it’s the kind of flex or counter-signalling that only true masters can really pull off properly.

On the piano, all of the black keys make up the pentatonic scale– so even if you don’t know anything about music, you can have fun playing around hitting random black keys and developing a sense of musicality that way. A person could conceivably do nothing but noodle on black keys for weeks and develop some interesting rhythmic and melodic sensibilities– if they’re really listening to what’s happening and allowing themselves to feel, and to learn. You can, through trial-and-error, figure out the melody to Amazing Grace on the black keys.

so i actually conflated a few things in this post here– scaffolding as in project management, and scaffolding-by-sketching, which I'll argue is part of project management. I didn't get around to making that part very clear, but I'm sleepy and tired and I figured I'd be happier to hit post than to leave it languishing in the drafts. This is itself sketchy business. I expect my next ~50-100 posts to be similarly sketchy and I am making my peace with it. gn

I liked, among other things, the observation that drafts aren't false starts but more like sketches. One thing that I've enjoyed doing recently is to write my sketches by hand, rapidly, in my very hard to read handwriting. Something about that makes me forget myself, because I can't easily see what I've written etc. And when something clicks, that becomes the scaffolding for a proper draft that I do on computer: I'll read the notes, type some as is, riff in new ways in other parts, skim and drop others, etc. I get into a more emotional, more playful flow that way, and still get some time to stop and think and try different approaches. Anyway, love seeing you feel your way forward here!