reality is unrealistic, take 1

people saying "be realistic" rarely actually mean "develop a more accurate model of reality"

I was doing an overview of the posts I’ve published on my Substack so far. I tried to get a sense of what my posts have been about, and what I want to be doing next. It feels like a lot of what I’ve written here has been about my creative process – which isn’t what I want to spend all my time writing about, but was probably what I needed to write when I wrote it. I do have other interests and curiosities I’d like to explore beyond myself, which I hope I’ll get around to soon.

That said, while doing the overview, a couple of phrases jumped out at me from previous essays – one was “funhouse mirror misunderstandings”, and another was “cartoon model of reality”, and I feel compelled to elaborate on that, because it feels both consequential and interesting.

None of us sees reality “as it is”.

“But please remember: this is only a work of fiction. The truth, as always, will be far stranger.”― Arthur C. Clarke’s forward to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

(A compelling case could be made that there is no such thing as a capital-R Reality, and really there are billions of different realities depending on your point of view. And that composite view is itself just another interpretation. All interpretations are wrong, some are useful, some will ruin your life.)

It’s worth noting that while there may be many competing realities, some are much, much harder to dispute than others. Napoleon successfully disputed the ‘reality’ that you can’t just become Emperor of France. But it was much harder for him to dispute the ‘reality’ that you probably shouldn’t invade Russia in the winter. A lot of life, it turns out, is about identifying which realities you can dispute, and which you can’t. And oftentimes you can’t really know until you try. And sometimes trying will get you killed. Be careful I guess? Good luck? Ayy lmao!

There’s a quote often attributed to Anais Nin: “We see things not as they are, but as we are.” As with most pithy quotes, the origin is somewhat messy and complicated, and to get meta about it, you get to decide for yourself which origin story you want to go with. Provenance aside, its a useful reminder that we are participants in our perception. How active or passive we are in that process is significantly (though perhaps not largely?) up to us.

What does it mean to “be realistic”?

Reality is often unrealistic. I love reminding people that “Donald Trump will become President of the United States” was generally considered unthinkably unrealistic even as recently as a year before he was elected. If you had tried to write him into say, a solemn TV show about US politics in 2010, you’d have been laughed out of the room.

Reality is often unrealistic. Our narratives are obliged to make some amount of sense to us, reality isn’t. And so truth is stranger than fiction. The map of New Orleans is “unrealistic” in many ways. Nintendo’s current CEO is Doug Bowser, sharing his last name with the main antagonist of the Super Mario franchise. There are many such ‘unbelievable’ facts when you go looking for them. Australia exports camels to the Middle East. Mozart wrote a song titled “lick me in the ass”. A grandson of Theodore Roosevelt named Kermit led the CIA operation to overthrow the democratically-elected government of Iran. On and on the list goes. These facts do not rely on their ‘believability’ to exist. Sometimes I joke that reality shops around for delusions to try on. It does seem like it. You might as well joke about outcomes you want.

To answer the question directly – I think when people say “be realistic”, they seldom actually mean “develop an accurate model of reality”. They typically mean something closer to “be more conservative”.

Jim Carrey: “My father could have been a great comedian but he didn't believe that that was possible for him, and so he made a conservative choice. Instead, he got a safe job as an accountant and when I was 12 years old he was let go from that safe job, and our family had to do whatever we could to survive. I learned many great lessons from my father. Not the least of which was that: You can fail at what you don't want. So you might as well take a chance on doing what you love.”

Obviously I’m not saying that everybody who tries their hand at comedy is going to end up with a Jim Carrey-sized successful career. Jim himself has spoken multiple times about how that’s not even the point. He’s also said, “I wish everyone could get rich and famous and everything they ever dreamed of so they can see that's not the answer.” And, alas, I have also recurringly seen that any time anybody successful warns about the perils of assuming success will satisfy or fulfil you, a subset of unsuccessful people find ways to dramatically, dazzlingly miss the point. And I’m not saying NOT to pursue success, either! I do think that it’s better to achieve some measure of success than not. But it’s not everything, and you should be very careful about what you sacrifice for it, because its pursuit can leave you hollow, despondent, and in some cases worse off than when you started.

Pursue what you pursue, but do it with your eyes open. Be wary of the seductive song of sirens that seek to exploit you.

The realistic are unrealistic

The thing that drove me mad when I was a teenager in school was how everything around me was based on implicit assumptions, social proof, authority and tradition. Hardly anybody around me seemed to care about actually thinking. About actually examining the reality we inhabited. Which might have been fine maybe a decade or two ago, but it was so obvious even to me, a child, that the world we were in was changing under our very feet, in front of our very eyes.

(The first questions to ask, of course, are what are we doing here? Why? How will that help? Why should I want that? What if I want something different? And these are all very inconvenient questions to ask in a classroom setting, even with well-intentioned teachers who are frazzled with having to stick to a lesson plan.)

As I’ve said elsewhere, and will write a separate essay about – when I was about 8 years old and I first sat at a computer and typed words into a forum and got replies from people elsewhere in the world, I swear on my life I instantly knew I had found The Holy Grail. The magical ability to being able to communicate with anyone anywhere for basically free is tremendous world-expanding magic. It blows open all of our inherited dogma, calcified intuitions based on older models.

Which reminds me of that story about grandma’s pot roast…

A young woman was hosting a dinner party for her friends and served a delicious pot roast. One of her friends enjoyed it so much that she asked for the recipe, and the young woman wrote it down for her.

Upon looking over the recipe, her friend inquired, “Why do you cut both ends off the roast before it is prepared and put in the pan?” The young woman replied, “I don’t know. I cut the ends off because I learned this recipe from my mom and that was the way she had always done it.”

Her friend’s question got the young woman thinking and so the next day she called her mom to ask her: “Mom, when we make the pot roast, why do we cut off and discard the ends before we set it in the pan and season it?” Her mom quickly replied, “That is how your grandma always did it and I learned the recipe from her.”

Now the young woman was really curious, so she called her elderly grandma and asked her the same question: “Grandma, I often make the pot roast recipe that I learned from mom and she learned from you. Why do you cut the ends off the roast before you prepare it?”

The grandmother thought for a while, since it had been years since she made the roast herself, and then replied, “I cut them off because the roast was always bigger than the pan I had back then. I had to cut the ends off to make it fit.”

So much of social reality is like this! To have to then sit in a classroom and endure lecture after irrelevant lecture was excruciating for me. If going to school was an actually effective guarantee of achieving your goals and desired outcomes, I’d probably have had a better time. And I think to some degree that might have been true for the previous generation. But everything is changing, and institutions are the slowest things to change.

The good news is that we don’t have to wait for institutions to change. We might not be able to make everything better for everyone everywhere all at once, but we can start by doing better for ourselves, and helping each other out with it, and then if we succeed at that, we will be able to acquire the resources and influence we need to impact successive layers, knock over larger dominos.

People get very attached to their models of reality.

“Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” – Philip K. Dick

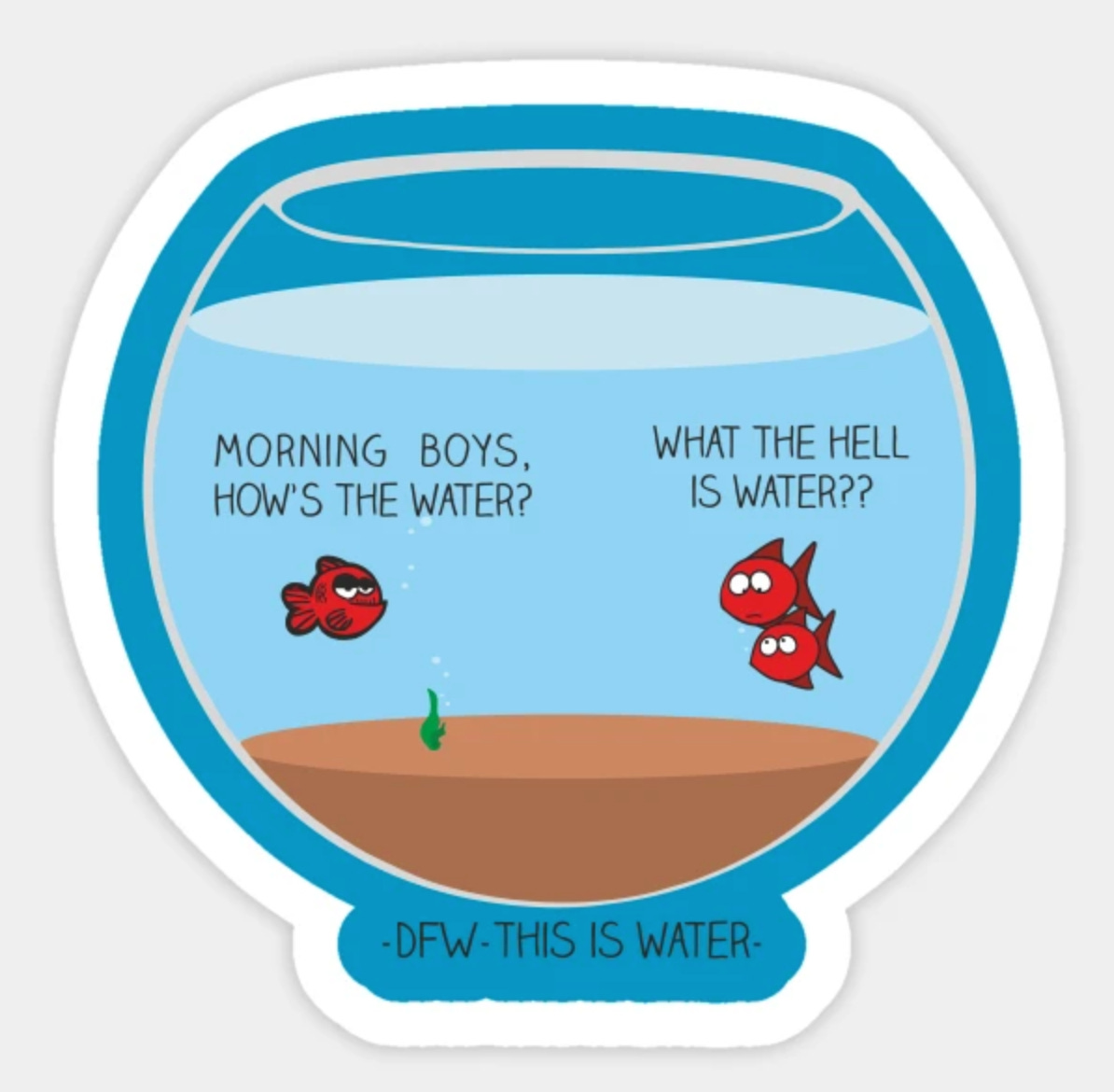

Often, as we’re living our lives moment to moment, we don’t even think to think of our models as models, or as representations, or as maps – we think that what we see is what it is. This is typically fine… until it isn’t. And when reality contradicts our models in a consequential way, we tend to experience some sort of crisis.

People sometimes describe it as like having the rug pulled from under them – a rug they might not even have realized existed, because it was always there and they never noticed it. Some people experience a rebirth, an initiation into a bigger, more complex world. Others desperately seek out a new simple narrative to cling onto, hoping that this time the new ingroup, the new talisman, the new ideology will be the solution to all their problems. Spoiler: It never is.

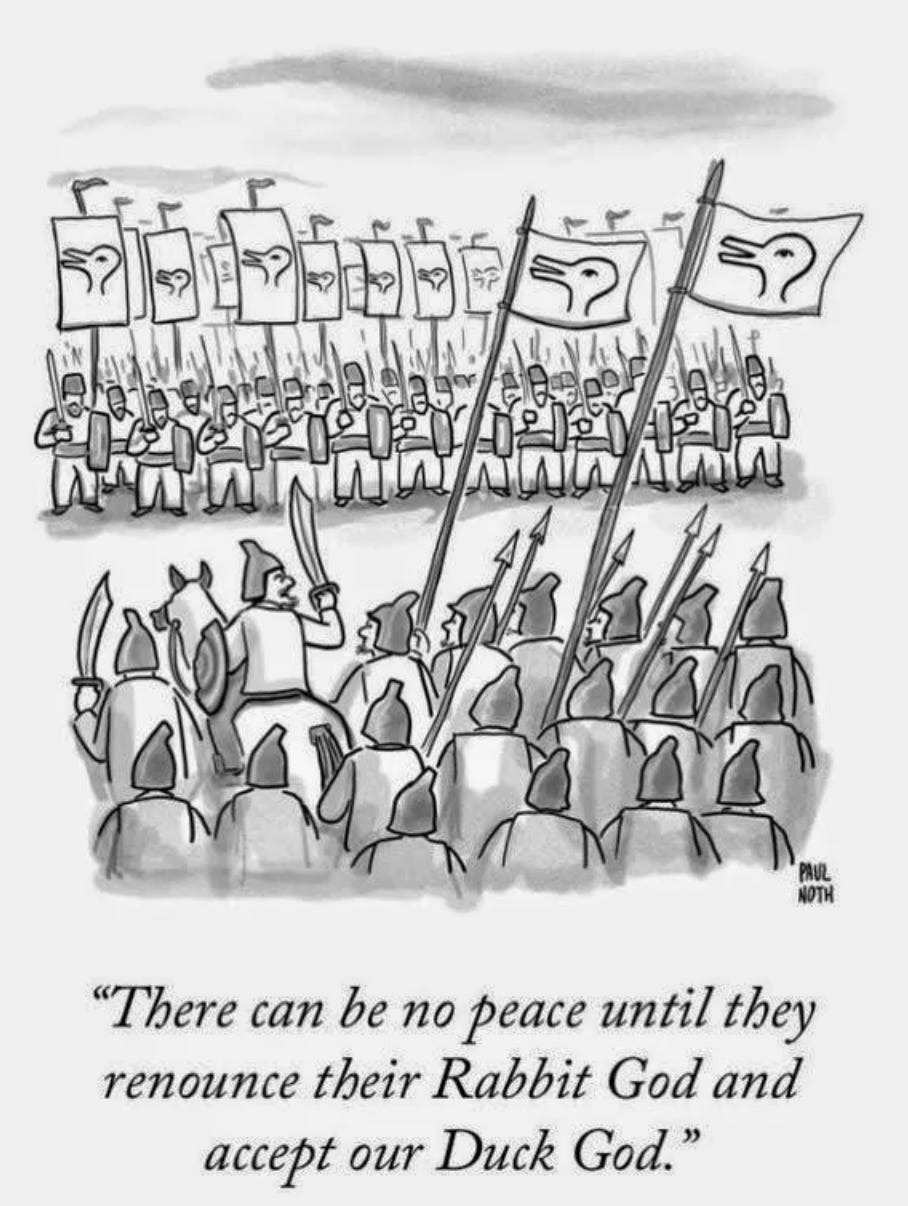

People even go to war over their competing models of reality.

“…we are all capable of believing things which we know to be untrue, and then, when we are finally proved wrong, impudently twisting the facts so as to show that we were right. Intellectually, it is possible to carry on this process for an indefinite time: the only check on it is that sooner or later a false belief bumps up against solid reality, usually on a battlefield.” – George Orwell, In Front Of Your Nose, 1946

I suppose the interesting and consequential question here is, what’s the difference between someone who updates their model when reality contradicts it, vs someone who doesn’t? How much of it is intrinsic, or genetic? How much of it can be learned? How much of it is a consequence of say, early childhood experiences?

I don’t have an elaborate, coherent theory, but what I’ve found to be helpful in my life is to look out for other people who get it, and to associate with them. Many of my favorite people are “ex-something”s. Ex-smokers, ex-Mormons, ex-lawyers. People who walked away from something that once defined their entire reality, and as a result had to rewrite their reality by themselves. It takes a certain courage to walk away from something that at one point meant a lot to you, and these people have both a lightness and a darkness about them. We know of loneliness, of despair, of betrayal, of kinship... and when we encounter each other in the wild we recognize each other by our scars, those of us who have broken our chains and escaped into the unknown.

✱

I’m going to end by being a bit dramatic, and taking a bit of poetic license to say something that isn’t absolutely true in a technical nitpicky sense – you’ll surely be able to think of exceptions and edge-cases – but I’ve found to be usefully-true-often-enough amongst the people who care to read my work. If it doesn’t apply to you, feel free to disregard it.

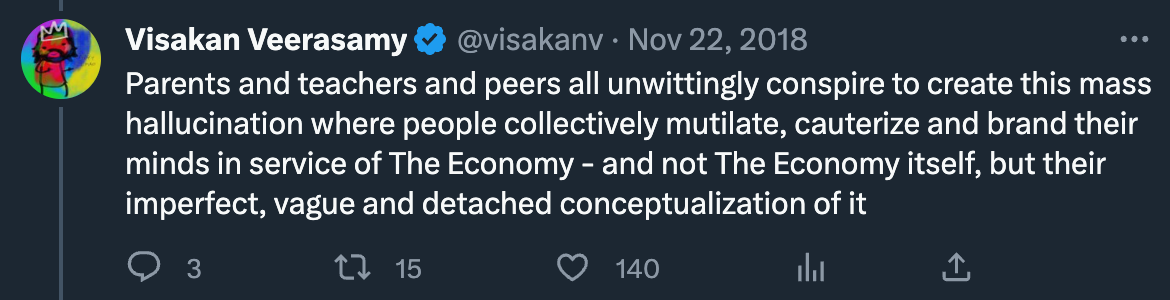

I have a lot more to say about everything, but I am getting tired and already this essay feels clunkier and more tedious than I would like. But the only way I’m going to get better at making this point in a beautiful, elegant way is to just practice saying everything in it, repeatedly. I want to end with a couple of my favorite tweets of all time:

The most magical thing about everyday life is how unmagical it seems. We are often at our most creative when we’re making excuses. Our minds are excellent machines at making things mundane, unsurprising, unremarkable. We tend towards homeostasis. We want to make life simpler for ourselves. Which is pretty reasonable, generally speaking. But in the process of doing so we often end up stripping away all of the magical detail in everything. We chafe from the tunnel-vision of excessive utilitarianism, start seeing everything around us in terms of their function, “what can this do for me”, rather than enjoying the infinite detail in everything – which is often the prerequisite to being surprised in interesting ways.

David’s tweet might not obviously-immediately fit the general theme of this “reality is unrealistic” essay. But I feel like it does, so let’s jam on it a little bit. It seems reasonable to assume that hard-to-solve problems (in the human domain) are just that: hard-to-solve problems. That is what they look like, that is what they feel like. So that’s probably what they are. Right? Sure.

But I’ve found, in multiple scenarios, that what people think their problems are, aren’t actually what their problems are. So while in a particular technical sense, yes, a hard-to-solve problem is hard-to-solve, it’s often because the problem is being misconceptualized, and approached in the wrong way. It can be ridiculously hard to push open a door marked Pull. And this can often be by design. It’s on purpose. Now, we can then get into some disputes about what exactly purposeful design means or looks like – and it’s precisely in that murky domain of unclear causality where the magic happens. In this case, a kind of dark magic, meant to absolve us of responsibility for outcomes, meant to keep us safe in familiar circumstances, where nothing too crazy will happen.

It seems kinda unrealistic to think that people might be doing these elaborate conspiracies with themselves (and others, actually!) to keep themselves kinda trapped in their circumstances. But I’ve come to believe it is often the truth. And if you say, “but Visa, if people turn out to be that capable, doesn’t that imply that we’re actually all so much more capable than we think we are, than we present to ourselves and each other, than we even believe?”

To which I can only say, yes, and now you know why I’m fucking crazy all the time.

1. The capacity of juggling multiple realities at once is the consciousness shift humanity needs. (While remaining roughly sane).

2. Truth is neither absolute, nor completely relative. It is layered. The deeper we dare go, the more depth we find.

Actually you were very coherent. The Self expressed by our worldviews needs to be constantly reinforced (it is then often described as the ego) because this is how it exists.

Without this reinforcement, there would be no Self. So people will tell themsleves whatever they need to stay in the worldview that keeps their Self intact, including the wrong conceptualization of their problems.

Now, the twist happens when you introduce doubt into that self<->worldview connection. If you allow for changing worldviews, you reach a new level of the game as you poin out.

So when thinking about problems, it becomes also possible to wonder “Am I actually conceptually wrong about what is wrong because I was wrong about a worldview before and this is a subset/smaller so I should allow for this”.

I find it interesting to play with what our minds are capable and feel like we’re just starting!