a funny pattern

on trying to be unpredictable

A funny pattern that has played out several times now: whenever I tell my wife that I’m going to bed to do some writing, I typically end up being distracted, scrolling twitter, playing online chess. Maybe I’d attempt some writing, but it would typically be too fragmented and disoriented to be ‘publishable’ by my own standards. On the other hand, whenever I tell my wife that I’m going to bed to sleep, it seems like more 80% of the time I end up writing something that I end up publishing.

What’s going on? I have a few overlapping hypotheses that come to mind. One is that I write better when I’m not trying to write. If I go to bed thinking “I have to do some writing”, it becomes somewhat heavy and wearisome. It feels like work, and not the fun kind. On the other hand, if.I go to bed thinking “I should go to sleep”, my mind lights up with “no, wait, not yet, let’s squeeze in a little writing first,” and then the writing is breezy and fun without the weight of obligation.

This whole system seems a little inelegant to me, but I’m at a place in my life where I’d much rather make use of an inelegant system that works, than strain myself to devise an elegant system that doesn’t work. “Inelegant” feels like I’m underselling it. It feels stupid. But I think about it and I have to concur: I would rather use a stupid system that works, than a ‘smart’ system that doesn’t. I’ll happily do this until I get to a point where… the joy of having published, feels like it’s less than the mild embarrassment of having had to ‘trick’ myself to do it.

ugh, he’s so predictable

I used to be averse to the idea of having some kind of ‘formula’ to my writing. And now I have to laugh a little bit that I ever felt that way. Because, sure, while I don’t want to be overly predictable, being completely chaotic doesn’t get you anywhere either. I tell this to my marketing clients all the time, so it’s funny to me that it’s taken me so long to internalize my own advice. You want to be at least moderately recognizable, so that people know what to expect, and then you experiment within that frame. I guess when I had the idea of doing an essay ‘era’ titled FRAME STUDIES, I got excited about the hypothetical possibility of changing the frame with every post. And maybe that’s something that can be assembled at a later stage, but my experience has been teaching me that you need to keep some things constant in order to really experiment. If you change every single variable in an experiment, you don’t learn anything. In fact, you typically want to isolate one variable at a time! So I have been going about my experiments in a very silly way, one that has mostly taught me how not to act.

When I think about it more, I realize I have been afraid of being predictable. I have been afraid of being typecast. I don’t want people to look at me and think they already know what I’m going to say. But my mistake is that I have been trying too hard to fight against that, trying too hard to be surprising. And there are few things less surprising than a person trying too hard to be surprising. Here’s a similar anecdote from Sylvester Stallone that I’ve been sharing a lot lately:

So, with all of that in mind, what should my next steps be? I should maybe just say out loud what are the things I’m nervous about or afraid of. I have several essay drafts and ideas that I’ve pedestalized in my mind as Important, and I’ve made very slow progress on them because I need them to be Perfect. And here I know exactly the right advice to take, because I’ve given it to so many people over the years and witnessed them flourish with it: do it badly on purpose. Again, there’s a pattern here where, trying to force it to be good, condemns it to being stiff, stale, mediocre. But try to make it bad-on-purpose– whether by using absurd premises, or a silly frame, or some other comical approach, and you’re far likelier to accidentally chance upon something fun.

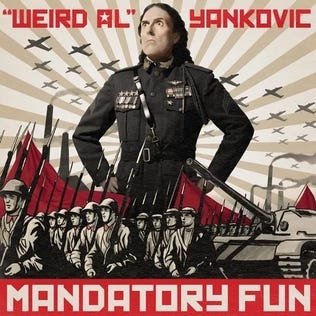

it’s a peculiar sort of wacko who makes it his job to have fun

Here I’m reminded that I’ve written one post on here titled Are you having fun, son? which was largely a recollection of my childhood memories of fun-having, and then I attempted to write a sequel, which I was dissatisfied with and posted it to my archives instead. I remember thinking that it’s so funny- both ‘ha-ha’ funny and ‘that’s weird’ funny– that having fun is so central to my life’s work, because it immediately throws it into this weird loop, this paradox, where… if your work requires that you have fun, can it really be true fun? But again, don’t people sometimes have fun at work when it’s not required? It’s the nature of ‘requirement’ that really muddies everything up. Which rhymes with the problem of neediness. It’s generally easier to have a good time with someone if you’re not needy about having a good time with them. On paper, the solution is simple: cease being needy! Remember that you’re going to die, remember that nothing matters, remember that the kingdom of god is already within you, have a laugh, see the joke of it all, ayyyyyy, lmao.

Sometimes this hits just right and you crack up laughing and the whole torment just falls apart. But sometimes it doesn’t work, and it can in fact make you feel worse. I’ve been on both sides of this. And lately… the more tired I get, the longer it’s been without me having any major wins, the harder it gets. And I’m so conflicted about how to present this in a way that is both honest and yet not… demoralizing? I think there are people who follow me on twitter who think that I never have any bad days.

And… it depends on what you mean by bad days, I guess. I had horrific days in my teens and early 20s, and I haven’t had one of those since I was maybe 27. But I do still get really depleted and down sometimes. Sometimes I feel like I haven’t really even gotten started on what I’m ‘supposed’ to be doing. Sometimes I feel like nothing I’m doing is working. I remember there were moments when I was quite miserable while struggling with working on Introspect, and when it got rough, I questioned whether a person experiencing misery even has the ‘right’ to write a book about introspection. But then… wouldn’t the opposite also be the case? If a person has never had rough days or experienced misery or depression or suicidal ideation, can they really be of service to someone who has? (I think the answer is yes, actually, but it’s not the same as with someone who understands.)

What does it even mean to have the ‘right’ to do something, anyway? It’s all made up, fictitious social rules that change on a whim. If we want to be serious in our craft we have to learn to have a moderate indifference to the social bullshit. This can be tricky because it can feel like– in my internal monologue I use the phrase ‘precious diva behavior’. And I’m conflicted about whether or not I am a precious diva, whether or not I want to be, whether or not I ‘deserve’ to be, whether or it not it is ‘good’ to be. I never want to hurt anybody else’s feelings unnecessarily, but some people will get upset just seeing you live your own best life. I ultimately made it through that conundrum by focusing on the fact that I was writing the book for a younger version of myself, and to that particular kid, hearing from me would be a god-send, regardless of my ‘qualifications’. We can move forward by attending to the past. And now that I have a child, in some ways it’s even easier: I can just act in whatever way I feel is the right way for my son’s father to act. And I suppose I could use that same reasoning in all of my work. If you wanna read someone more qualified, or someone more polished, then please go do that! I’m here to write for me, and for my people. Nobody can be everything to everyone.

a great blog makes for a mediocre book

I think it’s time I start wrapping up. I’ve talked about the pattern of my nighttime writing habits, the complications of mandatory fun, where do we go from here? I asked myself recently what would give me real relief, real satisfaction, and one thing that came up was, “publishing something that feels true to me, that I’ve never published before”. Could I possibly do it on-demand? The trick here I think is that it doesn’t have to be something dramatic or important. It can be something minor. And I find myself thinking, for some reason, about old blogs.1 I find myself thinking about the Nora Ephron movie Julie & Julia (2009), which as far as I can tell is the only major motion picture that’s significantly about a blog. I could go off on a tangent about how Nora Ephron was a real media theorist, and how her movies like Sleepless in Seattle (1993) and You’ve Got Mail (1998) each captured something unique and remarkable about the pinnacle of a particular media landscape. Sleepless was about radio talk shows, Mail was about chatrooms and email, and Julie was about a blog. While all of those mediums still exist, they all feel like they’re in decline, in contrast to the smartphone-era of Tinder and real-time texting and so on.

Anyway– super-quick recap of Julie & Julia – it tells two stories simultaneously, the story of Julia Child, who was famous in the 60s as a cookbook author and tv show host who introduced Americans to French cooking, and Julie Powell, a blogger who got popular for her live-blogging quest to make all of Julia Child’s dishes in 1 year. As a (former?) blogger myself, I was curious to look up more details about Julie Powell. It’s not surprising to me that the blog was popular– it’s a recurring motif I’ve noticed that people tend to be interested in interesting ‘expeditions’ where someone sets out to accomplish something challenging over a moderate length of time. But what’s fascinating to me is how– she then compiled the blog into a book, and it’s the book that Ephron’s movie was technically based on. And what really fascinated me were the reviews of that book.

via Wikipedia:

David Kamp writing in The New York Times disliked Powell's writing style, saying it "has too much blog in its DNA. It has a messy, whatever's-on-my-mind incontinence to it, taking us places we'd rather not go".

Keith Phipps of The A.V. Club did not think the transition from blog to memoir was handled well, asserting that its "digressive stream-of-consciousness style has become the lingua franca of the blogosphere, and while it can be an art form when dished out in daily installments, it's a slog at book length.”

This parallels perfectly with my sense that good twitter threads don’t translate easily into essays, because they’re written to fit the medium of twitter. They have ‘twitter grammar’. And I don’t just mean between the words of the text, but the stylings, the cadence, the tempo, everything. If you copy the text of a twitter thread and paste it into a blank white page, it feels ‘off’.

So what does it even mean to be ‘a good writer’? Every kind of writing is structurally different, and while there is something like a ‘general competence with words’, that alone does not guarantee that you will write good essays, or tweets, or books. People who are ecxeedingly specialized at one thing are rarely ever equally good at another thing. (Authors of popular books might get a lot of twitter engagement because they have a large fanbase, but that’s not the same as actually being good at tweeting. Not many people care about the subtleties of this, but I can’t seem to help obsessing over it.)

Anyway. It occurs to me that I’ve been approaching these essays/posts wrong. Because I’ve been prematurely thinking about how they will work together as a collection. Even though I try to conceive of them as essays, I’ve really been thinking of them as… chapters in a book. And books and essays are very different beasts. As evidenced by Julie Powell’s corpus, the things that makes a blog great, make for mediocre books. I’ve been struggling with a kind of premature optimization. Rather than try to design a grand overarching reader experience, I should focus on writing one standalone thing at a time, that works by itself, and to hell with everything else. It also occurs to me now that I’ve basically been overcorrecting because of my frustrations from when I was working on my book.

So, there we go. That’s something that feels true to me, that I don’t think I’ve published before. I’ve tried to write some version of this on multiple occasions, but I was never satisfied with it. I’m not satisfied with it now either, and I expect to write a better form of it in the future. But in the meantime, this is where I am.

i realize the connection between ‘thinking about old blogs’ and ‘patterns’ and ‘fun’ isn’t obvious. it goes like this… i used to blog quite effortlessly. i tweet quite effortlessly. a part of me believes that it should be possible for me to write substack posts with comparatively low effort. another part of me feels that that’s a self-serving bullshit feel-good belief, but i do think there’s a truth to it. it’s possible if i let go of the false assumptions that i have about what substack posts are supposed to be like. and i realize here i make a similar error to what i’ve seen people make re: youtube videos and podcasts and so on, which is assuming that things are supposed to have a high level of polish. but… polish is something that comes later. at least, that’s my view on it. some people have different views. it depends on your personal philosophy, your personal aesthetic sensibility. i believe- and it will take me a few months to prove this- that i CAN write effortless substack posts that meet my minimum threshold criteria for ‘good enough’, if i am willing to compromise on polish. that’s kind of what i was trying to get at with ‘resonance over coherence’. but like miles davis said, man sometimes it takes a long time to sound like yourself.

Here’s another funny pattern: Whenever I explain why I don’t feel like doing something, or how I’ve decided that I’m going to stop doing something, I often get a surge of renewed interest in doing it. Most recently this happened for me with chess. I literally wrote a twitter thread about how I couldn’t enjoy traditional chess very much because the outcomes in one game cannot directly affect another. Tweeting is preferable to me, because building a body of work is something that compounds over time, and you can reference other material that you’ve written before. Shortly after I wrote about that, I found myself curious to play chess again, and I’ve played over a thousand games on chess.com since.

I can think of other examples of this… when I say I’m going to organize my notes, I tend to waffle around. But if I say I’m going to delete notes… well. I’m going to try right now. I’m going to delete 5 bullets from my [[substack drafts]] roam page, just because… and… done. I didn’t just delete 5 bullets, I ended up reorganizing a whole bunch of stuff, probably for the better. Much to think about.

Fun read :) Felt quite disorganized while reading, but then it all came together in the last section in a nice way. I encounter a similar pattern to the one in this post in my writing all the time that I'm only slightly paranoid about, it goes like this:

When the writing is good, it feels effortless. The writing that feels hard, and cumbersome, and attached to details, and step-by-step always afterwards seems forced and rigid and lacking something. So is there any point in writing when it's hard? Or must one only wait for inspiration to strike?

I agonize about it. I must write -- but if I'm not already writing, is it not the right time? But somehow I must choose to start writing at some point...you get the idea.

I feel like the middle-ground I've come to -- and which you seem to also end up advocating -- is like, yes, you must force yourself to write somehow, whether its as part of an era, or This One Weird Bedtime Trick, but when you sit down to write, you have to be totally unbound to any particular thing. You have to just write what feels right. There's a symmetrical forcing of chaos on order: yes I will write at this time, but by god I am going to write whatever I feel like writing.

A good strategy for writing more, but one that fails often when confronted with longform content I find. So it goes.