resonance over coherence

something (deeply true) is better than nothing

A part of me thinks, it’s 327am, I’m tired, there’s no way I can write a good substack post in the next 10-15 minutes. But why do I think that? It’s because I have some assumptions in my mind about what a substack post is supposed to be. Why not try something different? Clearly, whatever I’ve been trying to do the past 4 months hasn’t been working, so I might as well try something different.

What does that mean, what does that look like? Well, some of the assumptions I’ve had are things like– for a substack essay to be good, it has to have a strong point-of-view. It has to make some sort of case, whether overtly or otherwise. It should be reasonably well-thought out, hopefully somewhat researched, hopefully links to a bunch of other things, so that it comes across as grounded, so that there’s heft to it. Those are rather reasonable things! But it’s possible to get swept up in a bunch of reasonable things into a position of stuckedness. And that’s exactly what I’ve done. Alright.

So how do I get unstuck?

I always find it easier to answer a question that arises from within, when I pretend that someone else asked me that question. The almost absurdly simple answer to “how do you get unstuck” is “get moving, in any direction you can”. Okay, what direction? Any direction! How do you choose? When you’re overwhelmed with possible choices, the first thing that comes to mind is as good as any. Just go. Now you’re moving. Now maybe we can get somewhere.

Where? Where are we trying to get to? “Away from here” is, again, simplistic, naive, but functional. It’s something. Alright. We have a bunch of words. A bunch of words invariably ends up sketching some sort of picture, whether you intend it or not. And we can examine that picture, and see what it tells us. Right now we have a portrait of a frustrated creative going off on a tangent. I can step outside myself and look at him go. Gosh, where is he going? He’s looking for something. What is he looking for? Normally this is where I might start second-guessing. But I’ve imposed a time-limit on myself, so I don’t have time to second-guess. What’s coming up? There’s always something. Life is too dense, too rich, for there to be truly nothing. What do I want to do? List out literally one thing.

A sense of resonance

One of the things that I really want to achieve with my substack posts is a sense of resonance. What do I mean by that? I want to feel like what I’m saying feels deeply true to me. What does that mean? There are things I mean by that phrase, that I haven’t actually articulated. Wonderful! We have ourselves a challenge, a puzzle to solve. What are the things I mean when I say “feels deeply true to me”, knowing that I mean something beyond the most literalist interpretation, for example saying “the sky is blue”? That’s true, but it doesn’t feel deeply true. It’s just, kinda true. Obviously true. Nondescript. Anodyne. Inert. I’m looking for something consequential, something that dislodges something within me, something that causes a dam to burst and for me to feel “holy fuck!” For it to go deep, maybe it has to be surprisingly true. And, gosh, surprise can be extremely context-dependent. Something that was obvious last year can be surprising today when you confront it unexpectedly. So, what’s surprising right now?

One of the things that I know to be true, believe to be true, feel to be true, is that my best work rarely ever happens on command. I rarely ever begin with an authoritarian assertion of “I should write an essay about X” and then go on to write it. My best writing almost always happens “by accident”. It happens “en route” to something else. There’s usually a sense of mischief, of goofing off. David Ogilvy said “The best ideas come as jokes,” so “Make your thinking as funny as possible.” He’s so right.

It’s hard to be funny when you’re being all solemn about some serious purpose. And yes, I know, I recently wrote a whole essay titled “Are you serious”. I will note that I was very careful to make sure to point out the solemnity trap in that essay. But it’s tricky business! This is where the surprise is. Simply being aware of the solemnity trap is not sufficient to stop you from falling right into it. In fact, there’s a meta-trap: the meta-solemnity trap is when you think, “Ah, yes, yes, the solemnity trap, I’m too good to fall for such a simple trap.” Next thing you know, you’ve spent months in twisted tension with seemingly nothing to show for it!

I’m being a little hard on myself there. It’s not true that I have nothing to show for it. I do have a lot of drafts. I’ve been publishing those drafts to my “archives” blog, which has been a source of relief for me. Why do I feel relief at publishing drafts to an archives blog that I don’t particularly intend to point anybody to? It’s one of the great mysteries of the creative process. I’m reminded of a story from Stephen Pressfield’s War of Art, where he describes being stuck for about 10 days, with the dishes piling up, and then eventually he sits at the typewriter, bangs out a couple of pages of nonsense, trashes those pages, and then notices his mood lifting, so much so that next thing he knows he’s whistling and cheerfully doing the dishes. It’s a story I find absolutely fascinating, which brings me to one of the things I’ve been meaning to talk about: possibility-space.

Possibility-space

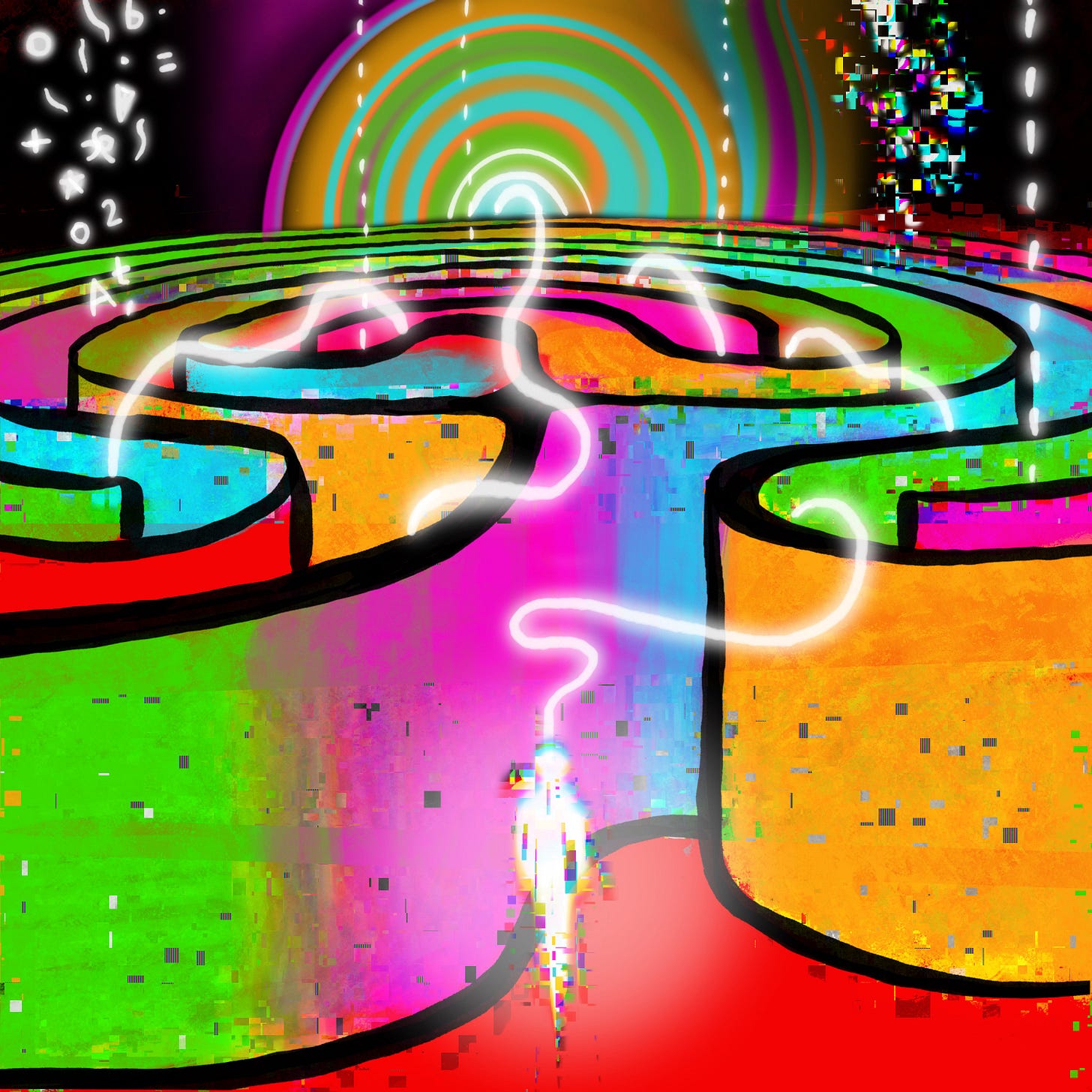

Possibility-space is simply the set of possibilities that we inhabit at any given point in time. The wild thing is that the possibility-space we experience, is typically smaller than the actual possibility-space that we inhabit. Our experience of possibility-space is constrained by our history, and our imagination. We’re unlikely to imagine ourselves doing something that we haven’t done before.

Until I started writing this particular essay, I was constrained by the belief that, oh no, I can’t possibly write a Substack essay in one continuous motion in a matter of minutes. That won’t be good. That won’t do. I was imposing constraints on myself, within myself. And the really subtle, tricksy thing is that I don’t typically experience these constraints as constraints. A person with collapsed awareness doesn’t think “man, my awareness is so collapsed right now.” We simply inhabit the limited awareness that we have, and in that moment, that just feels like all there is. Which feels ominous, constricted, desperate, overwhelming, and all-around not a good time.

So the big question is, how do we notice when we are in constrained possibility-space? My friend Michael Ashcroft likes to point out, we can only respond to what we notice. So how do we notice what we’re not currently noticing? And here I find that, I actually do have a whole bag of tricks, which I usually pull out when I’m trying to help somebody else, but am usually slow to pull out for myself. Which makes sense, because we can only respond to what we notice. When I notice that a friend is stuck, I leap into action to help. But when I’m stuck, I don’t quite notice that I’m stuck. As Pressfield says, procrastinators don’t say “I’m never going to write my symphony,” they say “I’ll write my symphony tomorrow.”

Silly little mental motions

What’s in the bag of tricks? It occurs to me that they’re all little ‘mental motions’, creative constraints that challenge us to think differently, see differently, act differently. The trick I’m using for this essay is “what if you just wrote something and published it without second-guessing it?” Maybe they can all be described in terms of questions. What if you inverted your assumptions? What if you made things harder for yourself? What if it were easy? What if you wrote about the thing you’re trying to write about? What if you used a different voice?

I’m reminded that Brian Eno has this deck of cards called Oblique Strategies. Examples from the Wikipedia page include,

Use an old idea.

State the problem in words as clearly as possible.

What would your closest friend do?

What to increase? What to reduce?

Are there sections? Consider transitions.

Try faking it!

Honour thy error as a hidden intention.

Ask your body.

Work at a different speed.

All of these can potentially be useful for helping someone get unstuck. It’s not that any particular prompt or suggestion has any intrinsic magical power to it. It’s that they have you looking at your work with fresh eyes. And looking at things with fresh eyes have a way of helping you notice things that you didn’t notice before.

I’m sure there are all sorts of other ways to challenge yourself to notice things. Doing it by yourself might be the hardest way to do it. Talking to someone else is often ideal.

People-shaped

I have a whole blogpost that I wrote once titled “talking for writers”, which I’d like to further develop into another essay about the power of making things “people-shaped”.

Ideas don’t always come to us people-shaped. Mine annoyingly tend to be sprawling, cantankerous monstrosities. But if we want our ideas to be of any use to anybody, including ourselves, we have to make them people-shaped. I believe this is a big part of why mythologies tend to anthropomorphize. People are very good at making sense of people, so if you pack an idea into a people-shaped container, it becomes easier for people to make sense of it.

Check out, for example, the above flashcards made by Kaycie D, who turned the clinical elements of the periodic table into memorable characters with distinct personalities.

I’m not saying every single idea should be turned into fictional character(s), but it’s certainly a powerful move if you choose to use it. “People-shaped ideas” can be broader than that, though. I mean it in roughly the sense that hammers and computer mice are designed to be grasped by the human hand. This is where appealing to human senses is also very worthwhile. I have a post I’d like to write about “Storytelling Heft”, referencing several bits of media that I’ve enjoyed recently. I have thoughts about how… food, for example, is something that’s very human. Everybody’s gotta eat, and everybody has memories and feelings associated with eating. So food is an excellent storytelling device. You can design a scene with characters eating, and have that tell the reader a tremendous a tremendous amount about everything and everyone involved. But more on that next time.

“Oof!”

It’s 415am, I’m running out of time and I’m running out of steam. I do a quick recap of what this post has been so far. I talked about the experience of being stuck and getting unstuck. I talked about possibility-space, and noticing, and things being people-shaped. I notice that I talked about “feels true to me”, and something was lacking about that. It occurs to me that “seems true” is not quite enough. It has to be something deeper, something more powerful. Something has to break, or click, there has to be something dynamic and magnificent, something has to HIT and make me go “Oof!” and then I know I’ve got it.

Was this essay perfect? No. Was it excellent? Eh. But am I okay publishing it? Yes… yes I am. It’s good enough. It gets the motor running. I have a separate essay to write about that. I have many different essays that I want to write about many different things. And if I can let go of my stubborn insistence that they have to be perfect, and simply delight in their music… if I can lead from the heart rather than the head, then maybe I can actually get around to writing them.

It is delightful to see you think in real time. It is a pretty strange sensation - it is kind of floating outwards, you don't know where you are going, there is a sense of a happening. It reminds me a bit of the feeling you get when reading Montaigne.

This essay reads so lightly and effortlessly! Is it just me, or do others feel like it too?